Lessons from the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

I've been curious about what changed after the last pandemic, the Spanish Flu of 1918. I remember in high school, not being a fan of history, and looked forward to college where I could elect to avoid the curriculum. This likely accounts for why the older I get, the more interested I am in all history. Learning about the Spanish Flu has been fascinating, and it's our topic this week.

Medical scientists agree that the Spanish Flu was an H1N1 influenza virus that originated in birds and likely crossed over (mutated) through animals. They believed possibly pigs, horses, or maybe cattle could have been the conduit that enabled this deadly virus to transfer to humans.

Throughout the world, each year, new cases of the flu occur, often a mutant derivative of previous viruses, or as an entirely new strain. But this was different; it did attack the lungs, cause pneumonia and other respiratory illnesses, but the affected were predominantly younger people, often men (though the ratio between sexes would balance out by the end of the pandemic) between the ages of 20 and 40. This occurrence was for two reasons; first, WWI was in full swing, and soldiers the world over lived, bunked, and fought close together. Second, this generation had never been exposed to an earlier, less deadly virus that their elders had experienced decades prior. Unlike with Covid-19, the older generation had already developed immunities that would make them resistant to the Spanish Flu.

Young men would arrive in the morning with flu-like symptoms and be dead by evening. All totaled, 675,000 Americans would lose their lives along with 20M to 50M people worldwide in just over a year. A statistic that is difficult to fathom when you consider global travel was in its infancy, as only 15 years earlier, the Wright brothers conducted their maiden flight.

That is a 30M person delta; it's pretty hard to be off by that much with something as simple as counting the deceased. More on this later.

April 5th, 1918, Dr. Loring Miner documented in public health reports the first cases of the virus. Eighteen people came to a hospital in Haskell County, Kansas, with severe flu, and by the end of the day, three had died. The doctor had never seen anything like it before. Haskell County was a small farming community, and historians believed its reliance on farm animals could have provided the virus a platform to jump species.

Just 300 miles away from Haskell was the US army training base, Camp Funston. Camp Funston housed over 40,000 soldiers; many would frequent the town when on leave. Records would show that in March, soldiers were experiencing severe flu and pneumonia, but this did not deter the Army from deploying them back to their home bases and throughout Europe to fight in the war.

The virus spread aggressively throughout France, Spain, Germany, and the UK from April to June when miraculously, in July, it had almost entirely disappeared. It was Summer, and as we know, flus don't fare well in the warmer months. Yet, people were still carrying the virus inside their bodies; it laid dormant until the fall when a mutated, more deadly version arrived. In late August, at Fort Devens in Boston, the disease again surfaces, close to 14,000 soldiers got sick, and 800 died. Shortly thereafter, two men arrived with the virus at Camp Dodge in Iowa; six weeks later, 12,000 men had become infected. By Christmas, it would spread from base to base and city to city around the world.

"The rapid movement of soldiers around the world was a major spreader of the disease" James Harris, Historian, Ohio State University

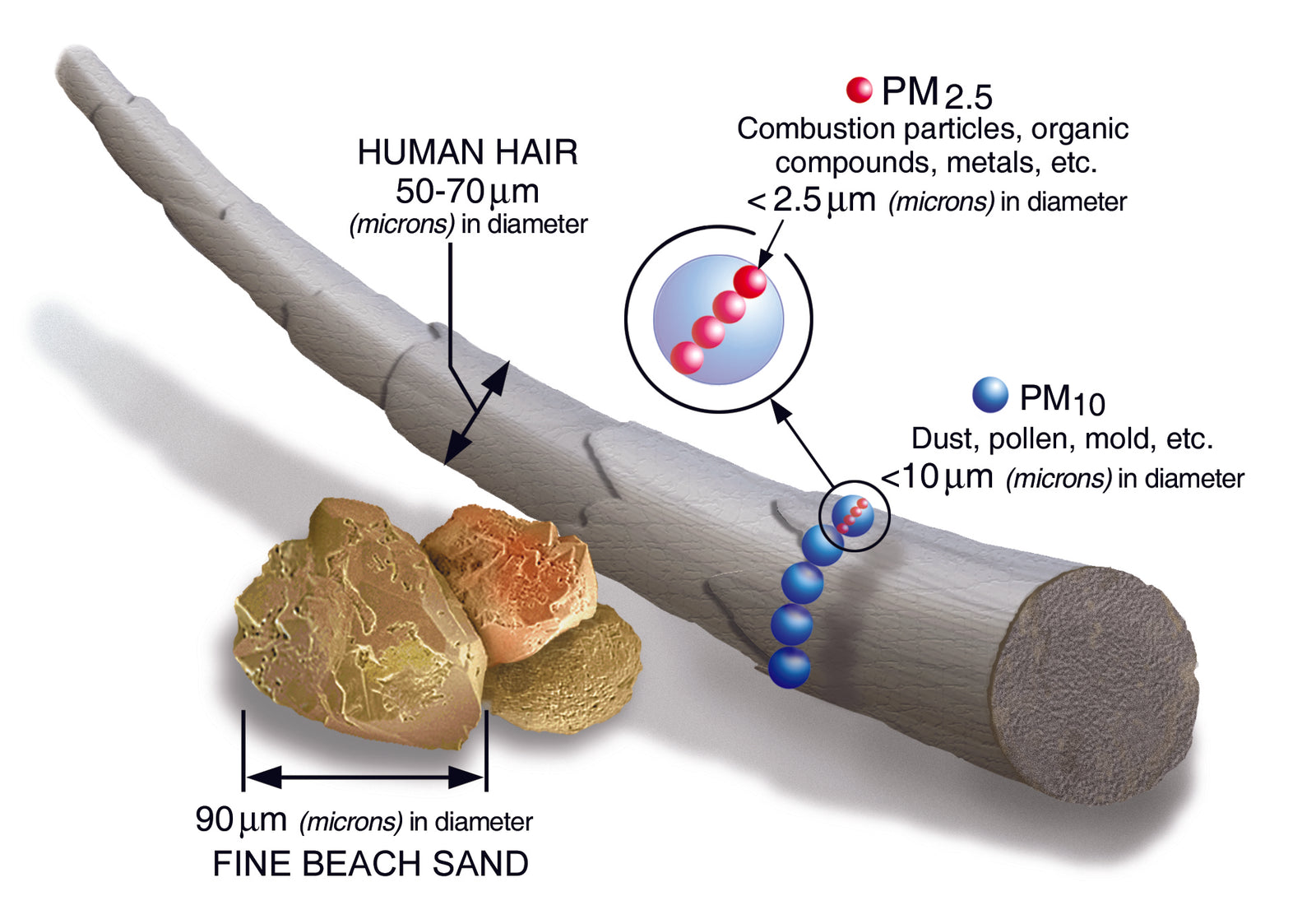

Like Covid-19, it was believed the virus spread through the air, but also through food, saliva, and items touched and shared. Patrons had to wear masks, stay at home, and social distance. Restaurants, bars, schools, colleges were closed (and yes, it was as political then as it is today). You were not allowed to spit, sneeze or cough without covering your mouth with a handkerchief and if you were to kiss, it was recommended to kiss with a handkerchief between your mouths.

Regarding the possible 30M unreported deaths, with World War !, still in full swing (albeit in its waning months), nations were reluctant to report deaths associated with the war, virus, pneumonia, or anything else that might impact morale, and of course, for political purposes. Spain, however, a nation neutral in the First World War, reported daily the names of those individuals that had passed. This reporting led the world to the belief that Spain was the source of the pandemic, though they had no soldiers being deployed anywhere in the world.

I chose this topic to write about not just because it's relevant but because I continually imagine what the world will look like in the months and years ahead. The pandemic of 1918 gave us handkerchiefs as fashion accessories, wash your hands as a mandate to avoid colds and flu, and of course, the portable spittoon to avoid being fined for spitting in the street.

I was listening to an interview with the CEO of Blue Apron, Linda Findley Kozlowski. She was discussing the changing needs of a socially distant, stay at home community, and customer base that now relies on good food to be delivered directly to their homes. She got me thinking, the notion of groceries, personalized menus, and even the public's increased confidence that they can prepare and cook tasty and creative food at home is likely to become yet another new normal.

Perhaps UV technology fits into the long-term plan of solutions that will help prevent the spread of colds, cases of flu, and other diseases in the future. Or maybe our UVC/Ozone disinfection box goes the way of the portable spittoon. What I am confident in is that the new normal isn't just about virtual communities, zoom video calls, and curbside pickups. Instead, we are likely to see a wave of innovative thinking here in the US and abroad that will require us to change old habits and develop new ones.

Interestingly, what followed the pandemic of 1918, was the roaring 20's, one of the most prolific periods of growth in American history, but that's another story.

Also in News

An Unusual Journey to Normalcy

The History of Vaccines: What it Means for Coronavirus