The History of Vaccines: What it Means for Coronavirus

Years ago, I had a job that took around the world to host technology exchanges with governments, telephone service providers, and high tech companies. I'd host day-long events with industry experts talking about how technology was going to change our lives and the world for the better. One of the gentlemen that sometimes participated in these events always had a refreshingly different perspective. I was always amazed by his ability to discuss the past to help our audience better see the future.

With the vaccine well on its way to approval, I thought I’d write about the history of vaccines. I remembered that if there is a person who could do this topic justice, it would be my good friend, Bill Petro. Bill is a professional speaker, blogger, and historian and has agreed to share his thoughts on the topic.

On November 30, Moderna announced that they are submitting their Coronavirus vaccine to the Food and Drug Administration for Emergency Use Approval. On November 20, Pfizer and BioNTech announced the same.

What are vaccines, when were they first developed, and what is the road to an approved vaccine in today's world?

"Vaca" in the word vaccine sounds like "cow." The word comes from the Latin phrase Variolae vaccine, meaning the "smallpox of the cow," and referred to cowpox. What does vaccination have to do with cowpox?

Edward Jenner, in 1789 was working on a way to treat the deadly smallpox pandemic. This particularly deadly killer had killed almost half a million Europeans during the 1700s and 1800s, and perhaps as many as 300-500 million people worldwide over its almost 500-year history. The story goes that when Jenner was a 13-year-old orphan boy and apprentice to a country surgeon, he'd overheard a beautiful milkmaid's boast. She had a "peaches and cream" complexion that was flawless and bragged:

"I shall never have smallpox, for I have had cowpox. I shall never have an ugly pockmarked face." Edward Jenner

Jenner, who became a British physician and scientist, tested his theory that cowpox exposure would protect people from the deadlier smallpox by taking the pus from a cowpox pustule and vaccinating a young boy. After the boy proved immune, he further vaccinated several other children, including his 11-month-old-son. He successfully developed an effective vaccine against smallpox in this way, the first of its kind, and was aptly called "the father of immunology."

Vaccines vs. Inoculations

At this time, smallpox inoculation was not new and was standard practice, having come to England some 68 years earlier from Constantinople. Variolation, one popular form of the practice, had a serious downside. Variolation involved taking material from another person already infected with smallpox and transferring that to the patient in the hopes of producing a mild infection and an immune response.

This practice, originating in China years before, had passed through the Middle East before coming to England, Europe, and eventually America. George Washington ordered the Continental Army to be variolated. Early 18th-century Puritan pastors like Cotton Mather in Boston and Jonathan Edwards at Princeton popularized the practice. Edwards caught the disease but did not survive it. Edward's daughter Ester and her husband, Reverend Aaron Burr, Sr. also succumbed to smallpox.

The danger of variolation is that it makes the patient contagious with smallpox until they develop their own antibodies, possibly infecting others. Additionally, without standards of dosing or properly skilled physicians, it could kill the variolated patient. Ultimately the collateral smallpox cases caused by variolated patients immediately after inoculation eventually outweighed the benefits, and vaccination ultimately replaced it. - Cotton Mather

Vaccines' Benefits

Vaccination, in contrast, had the benefit of not infecting others beyond the immediate subject because it was made from the weaker cowpox. Edward Jenner first used it in 1796. In 1967 a global effort of higher vaccine production and needle technology advancements led to the eventual elimination of smallpox in 1979, according to the World Health Organization (WHO.)

Louis Pasteur honored Jenner by broadening the term "vaccine" to refer to the artificial induction of immunity against any infectious disease. Pasteur and his successors created vaccines for Diphtheria, Measles, Mumps, Rubella, and Influenza. - Louis Pasteur

Vaccines' Development

Vaccines typically take 10-12 years to develop and sometimes as long as 20 years to perfect. A vaccine is rarely developed in less than five years. With a tip of the hat to Star Trek's faster-than-light travel, Operation Warp Speed is an American government program that has funded billions of dollars for medical research to develop and manufacture a vaccine for the Coronavirus pandemic.

Today, there are government controls in the United States that guide and define vaccines' development and deployment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has defined the multiple stages of vaccine development. In their clinical development stage, there are three trial phases. The crucial phase is Phase III that 10s to 100s of thousands of people (typically 30,000) who test the vaccine for efficacy and safety, studying control groups with placebos and any adverse effects or rare side effects of the vaccine. Typically, a minimum of 40 days after the booster (second) shot is required for testing efficacy and side effects. There may also be a period of peer reviews of the study. After a successful Phase III trial, the vaccine developer will submit a New Drug Application to the FDA.

Vaccines for COVID-19

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for regulating vaccines in the U.S., including manufacturing and quality control tests for release. This includes the vaccine's safety and ability to elicit a protective immune response in animal testing, in addition to proposed clinical protocols for studies in humans. Earlier this year, the FDA issued guidance, adding 60 days of testing safety data for Coronavirus trials, before approval. That is yet to be determined. Why?

When will we have a COVID-19 vaccine?

Until now, there are no vaccines that met the requirements described above. There are over 100 studies currently underway. Biotech candidate trials up to now in America have not yet been successful.

However, biotech companies Pfizer and Moderna, based on partnership with German biotech firm BioNTech, have announced promising vaccine candidates with greater than 90% effectiveness, but neither had completed Phase III testing nor undergone peer reviews.

Either company may file with the FDA for an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), which short-circuits the usual strict requirements for vaccine trials and lowers the bar for approval. Pfizer and BioNTech announced their intention to do that, as now Moderna has as well. Soon others will do the same. Even after FDA approval, there are manufacturing, distribution, and deployment phases.

So far in the U.S., there have been over 12 million cases and over a quarter of a million reported deaths. But there is hope.

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

www.billpetro.com

Bill is a freelance blogger and is available for hire; contact him if you're thinking about creating a blog or newsletter for your business.

Thanks, Bill!

Also in News

An Unusual Journey to Normalcy

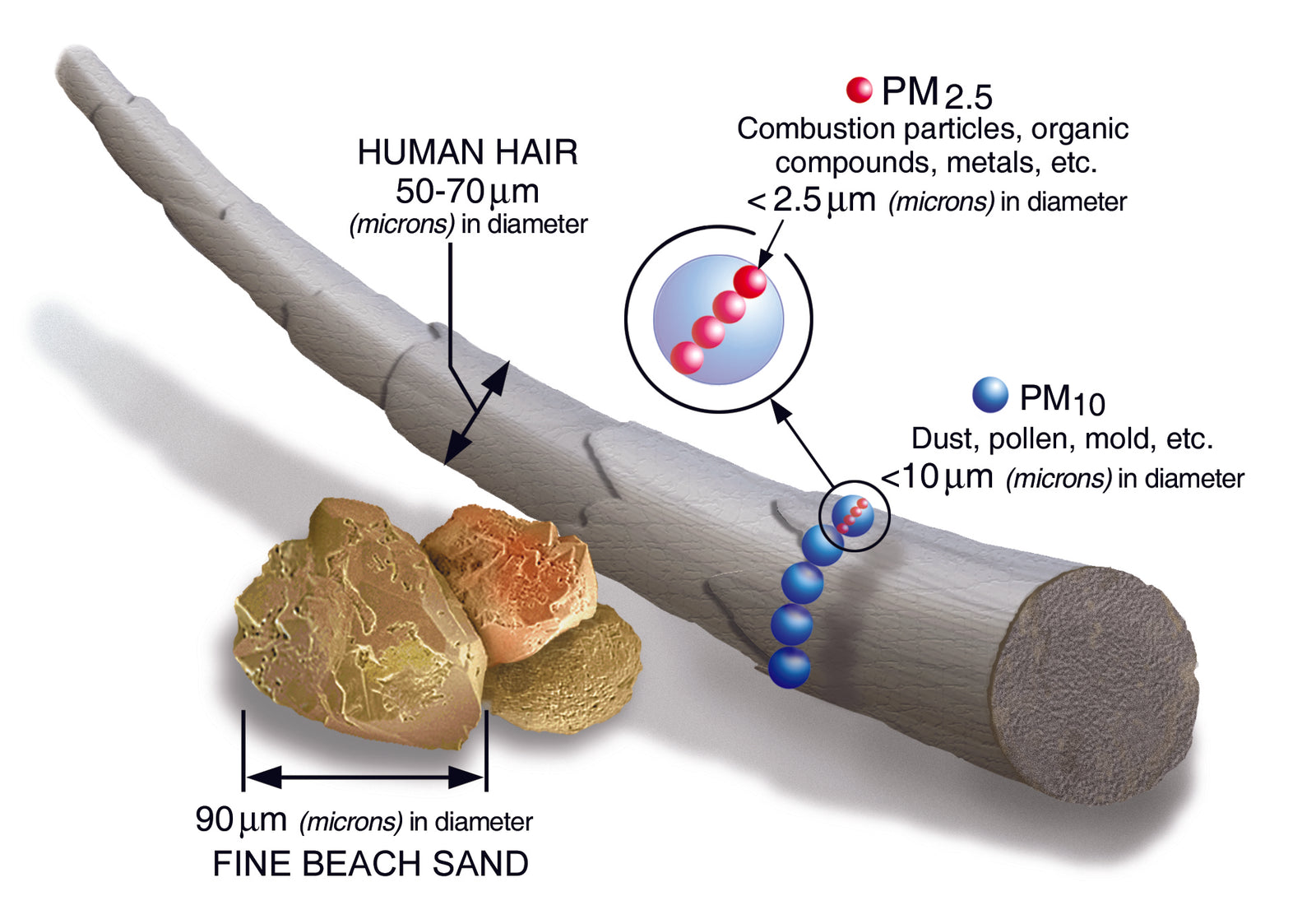

Size Matters